Why the future belongs to humans working with AI and not competing against it

1. Introduction: The AI debate has become intellectually lazy

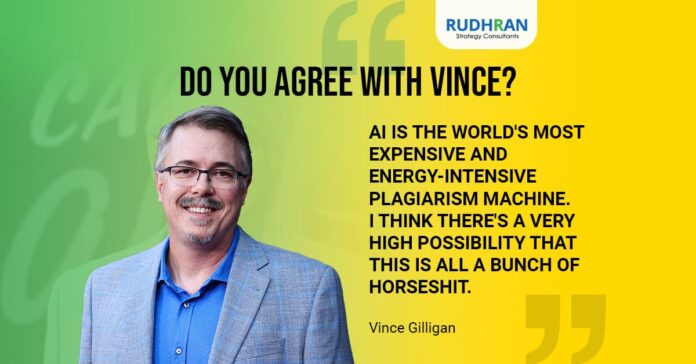

When Vince Gilligan – the popular Director of Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul series – described artificial intelligence as “plagiarism machine,” the reaction was immediate and polarized. Creative professionals applauded him for defending originality. Technologists dismissed him as reactionary. Business leaders largely ignored the nuance and continued to pursue AI-led efficiency narratives.

All three responses missed the deeper issue.

Gilligan was not making a narrow complaint about technology. He was expressing a civilizational concern — about authorship, accountability, and the erosion of human agency in systems that increasingly shape creative, commercial, and social outcomes. At the same time, a parallel but equally shallow narrative was taking hold in Big Tech boardrooms. Large enterprises, pressured by investors and emboldened by aggressive messaging from AI technology companies, began treating AI not as a tool to augment decision-making, but as a justification to replace people.

Layoffs were framed as transformation. Reduction was framed as innovation. Speed was confused with wisdom. What followed over the next two years should not have surprised anyone with real operational experience:

- Customer experience deteriorated in subtle but measurable ways

- Internal decision quality declined even as dashboards became more sophisticated

- Exception handling costs increased

- Rehiring quietly began — often at higher cost

Yet public discourse did not mature. Instead, it hardened into extremes. On one side emerged AI absolutism – the belief that human judgement is inefficient, emotional, and ultimately inferior to algorithmic optimization. In this perspective, humans are legacy systems — soon to be obsolete for work.

On the other side emerged AI rejectionism – the belief that AI is inherently derivative, unethical, creatively bankrupt, and incompatible with serious intellectual or artistic work. Both positions are comforting, but RSC (Rudhran Strategy Consultants) argues that both viewpoints are wrong. They are comforting because they absolve responsibility. They are wrong because they misunderstand how value is created in the real world. The truth — uncomfortable, unmarketable, and far less dramatic — is this:

AI does not replace intelligence. It replaces friction.

This distinction is where most organizations failed. AI systems are extraordinarily good at producing outputs. They are extraordinarily bad at understanding outcomes. They do not know which decisions will survive contact with reality, politics, regulation, culture, ethics, or human emotion. They do not understand regret. They do not carry consequences. Humans do. And this is why the central question of the AI era is not technological. It is governance-driven:

- Who frames the problem?

- Who decides what “good” looks like?

- Who is accountable when something goes wrong?

These questions cannot be delegated to machines — no matter how advanced. The mistake of the last two years was not that enterprises adopted AI. It was that they adopted it without humility. They assumed intelligence was transferable without judgement. They assumed efficiency could exist without context. They assumed automation could substitute for experience. In doing so, they misunderstood both AI and themselves.

This article does not argue against AI. It argues against intellectual laziness masquerading as progress. It takes a position that will become increasingly difficult to ignore such as:

- AI is not the author of meaningful work. It is the amplifier of human intent — good or bad.

- Used without experienced human direction, AI produces noise at scale.

- Used with discernment, it produces outcomes previously impossible.

The future will not be decided by those who are for AI or against AI. It will be decided by those who understand when to trust machines, when to override them, and when to slow down instead of speeding up, and this is a conversation worth having, and that is the conversation this article will pursue.

2. Why the “for AI” vs “against AI” framing is fundamentally wrong

The most damaging consequence of the AI hype cycle is not technological misunderstanding — but rather it is the conceptual laziness. Across media, corporate communications, conferences, and even in policy discussions, AI is framed as a binary choice:

- Or you are against AI

- You are either for AI

This framing is not accidental. It is convenient. It simplifies complex questions into marketable positions. It creates camps, narratives, and urgency. Most importantly, it removes the burden of thinking deeply about how work actually gets done. Shouldn’t this be obvious? In reality, no serious professional problem has ever been solved by ideological allegiance to a tool. Either humanity has lost its capability to think analytically, or Big Tech companies have strong PR’s that drive their narratives efficiently without justification.

Organizations that declare themselves as “AI-first” without defining “first–in-what-sense” are no different from organizations that once declared themselves as “digital-first” without understanding what digital actually changed. In both cases, the label substitutes for strategy. Pure sensationalism is valued without definition, meaning, or purpose. To understand why the “for AI vs against AI” framing is flawed, we must first confront a basic but uncomfortable truth:

AI is not an actor in the system. It is an instrument within a system and instruments do not make decisions. People do.

2.1 The myth that intelligence is purely computational

The “AI-will-replace-humans” argument rests on a deeply flawed assumption that intelligence is primarily about computation — processing speed, memory, and pattern recognition. If that were true, spreadsheets would have eliminated finance professionals decades ago. Calculators would have made mathematicians redundant. Databases would have replaced analysts. None of this happened. Instead, what changed was the nature of human contribution.

As tools became more powerful, the value of judgement increased, not decreased. Professionals were no longer paid for calculation. They were paid for interpretation, prioritization, and decision-making under uncertainty – all human-centric elements. AI follows the same trajectory — but at a larger scale. What AI automates is not intelligence. It automates mechanics that include:

- Drafting

- Summarizing

- Comparing

- Simulating

- Repeating

What it cannot automate is accountability and responsibility. Every meaningful decision in business, creativity, governance, or medicine carries consequences that extend beyond the output itself. Someone must answer for those consequences. AI cannot, and never will. The moment an organization forgets this distinction or its accountability, it begins to behave irresponsibly — often without realizing it.

2.2 Why AI absolutism fails organizations and real-world applications

AI absolutism — the belief that AI should replace human decision-making wherever possible — thrives in controlled environments:

- Demos

- Pilot projects

- Investor decks

- Narrow use cases with clean data

- Proposals

On the contrary, AI collapses in real world application and organizational decision-making because they are beyond controlled environments owing to:

- Political systems

- Cultural systems

- Regulatory systems

- Human systems

- Macroeconomic systems

- Geopolitical systems

Real-world contains ambiguity, conflicting incentives, legacy constraints, and informal power structures that never appear in datasets. AI can optimize for what is visible. It cannot reason about what is unsayable, or implied by power structures and office politics. When AI absolutists argue that humans are inefficient, what they perhaps imply is that humans are inconvenient.

Humans question assumptions. They resist bad, unethical, or immoral decisions. Most importantly, humans notice when something “doesn’t feel right” even if the numbers look correct. Those frictions are not bugs. They are safeguards encompassed by empathy and discipline. Enterprises that remove those safeguards in pursuit of speed eventually discover that speed without direction is not progress, but rather acceleration toward failure.

2.3 Why AI rejectionism is equally misguided

At the opposite extreme is AI rejectionism — the belief that AI inherently degrades creativity, ethics, or intellectual integrity. This position often comes from understandable fear:

- Fear of deskilling

- Fear of plagiarism

- Fear of loss of authorship

- Fear of irrelevance

- Overall, the fear of becoming insignificant or losing jobs/livelihood

But rejecting AI outright is also a strategic error. Every profession that refused to engage with new tools in the past eventually found itself marginalized — not because the tools were perfect, but because others learned how to use them responsibly. Rejecting AI does not preserve human excellence. It isolates it. The critical distinction is not use vs non-use, but uncritical use vs governed use.

AI does not corrupt creativity or destroy thinking. Lack of judgement and delegating thinking is what destroys creativity.

2.4 The real axis of the debate: Accountability, not capability

The correct way to frame the AI question is not ideological, but operational. The real axis is this:

- Who frames the problem?

- Who validates the output?

- Who owns the consequences?

- Who intervenes when reality diverges from prediction?

These are governance questions, not technical ones. Any organization that adopts AI without answering these questions is not innovating. It is gambling or worse, falls under the FOMO category. The latter is far worse because organization are merely exercising the rat-race mentality under the veil of insecurity. And this is precisely where many large enterprises erred over the last two years.

They treated AI as a capability upgrade, when in fact it was a decision-making amplifier. They increased the power of the system without strengthening the judgement guiding it. This is why layoffs framed as “AI transformation” were often misguided. They removed human judgement at the exact moment when stronger judgement was required.

2.5 Why the middle ground is discipline and not a compromise

There is a temptation to describe the human + AI position as a “balanced” or “moderate” view.

That would be inaccurate. The middle ground is not a compromise between extremes. It is a disciplined stance that demands more from leaders, not less. It requires:

- Clear articulation of objectives

- Explicit boundaries for automation

- Defined escalation paths

- Human override mechanisms

- Accountability frameworks

- Uncompromised ethical standards

This is harder than blind optimism or outright rejection. It requires leaders who understand both the power of tools and the limits of abstraction. The future will not belong to organizations that are “AI-first.” It will belong to organizations that are judgement-first and AI-enabled.

And this distinction will separate those who create value from those who merely chase the next “sensational’ headline.

3. “Plagiarism Machine:” Why the criticism is valid — and insufficient

When Vince Gilligan characterized AI as “plagiarism machine,” he articulated something many professionals intuitively feel but struggle to explain – that AI-generated outputs often resemble competence without originality, structure without soul, and fluency without intention. This discomfort is not imaginary. It is structural. AI systems are trained on vast corpora of existing human work — scripts, essays, designs, strategies, reports, conversations. They do not “experience” the world. They infer it statistically. They do not originate ideas, but merely extrapolate from precedent. In that sense, Gilligan’s phrase is accurate because AI is, by design, a derivative.

But here is where the debate often stops — and where it becomes misleading.

To label AI as “plagiarism machine” and conclude that it therefore has no legitimate role in creative or intellectual work is to misunderstand both plagiarism and creation.

3.1 All learning is derivative — creation is selective

Every human creator learns by absorbing the work of others. Writers are voracious readers.

Filmmakers watch a lot of films for inspiration and learning. Consultants study past cases. Scientists build on prior research, intuitively called as prior art. Originality has never meant creation from nothing. It has always meant selection under constraint.

The difference between a novice and a master is not access to material. It is discernment.

AI lacks discernment. It does not know which ideas are tired, which are dangerous, which are politically infeasible, which are ethically unacceptable, or which are contextually inappropriate. It does not understand timing or consequence. It produces outputs that are statistically plausible — not strategically sound. This is the primary reason why AI-generated work, especially on the creative side, feels hollow owing to lack of meaning and direction.

3.2 The real danger is not plagiarism — it is avoiding responsibility

When professionals present AI-generated outputs without critical intervention, they are not outsourcing creativity — they are outsourcing responsibility. They are allowing probability to masquerade as judgement. This is where enterprises made a profound error. They treated AI as a source of answers rather than a generator of options. They accepted outputs without interrogating assumptions. They allowed fluency to substitute for understanding.

In doing so, they weakened their decision-making.

4. What AI actually does well — and what it never will

One of the most damaging effects of the AI hype cycle has been the blurring of capability boundaries. AI has been spoken about as if it is a generalized intelligence, when in reality it is a highly specialized system with asymmetric strengths and weaknesses. Enterprises that failed to understand this asymmetry made poor decisions — not because AI is weak, but because they assigned it responsibilities it was never designed to carry.

AI’s genuine value lies in acceleration, not judgement. AI will excel in:

- High-speed information processing

- Pattern recognition at scale

- Drafting and synthesis

- Hypothetical scenario generation and simulation

- Removal of execution friction

What AI categorically does not do based on human experience include:

- Develop intention

- Contextual judgement

- Ethical reasoning

- Risk ownership

- Discernment based on circumstance

5. The AI-led layoff wave: what actually happened

The most visible and consequential manifestation of AI hype over the past two years was not new products, breakthrough use cases, or sustained productivity gains. It was corporate layoffs.

Across technology, finance, SaaS, media, and large enterprises, workforce reductions were justified using a familiar set of phrases:

- “AI-driven efficiency”

- “Automation-led operating model”

- “Reallocation toward AI initiatives”

- “Flattening layers enabled by AI”

In public communication, these moves were framed as strategic foresight. Internally, they were often driven by urgency — fear of being left behind, investor pressure, and an untested belief that AI could immediately substitute for human capability at scale. To understand what went wrong, it is essential to separate what companies said from what AI systems were actually ready to do.

The table below captures a snapshot of large, internationally visible enterprises that announced significant layoffs. This is not an exhaustive list. It is a signal sample — sufficient to reveal patterns.

| Company | Approx. layoffs | AI-linked rationale cited | Primary roles affected |

| Amazon | ~14,000 | AI efficiency, automation, cost optimization | Corporate ops, program managers |

| Microsoft | ~9,000 | AI infra focus, restructuring | Product teams, engineering layers |

| Salesforce | ~4,000 | AI agents replacing support functions | Customer support, support engineers |

| Meta | ~600 | AI unit reorganization | AI infra, research, product roles |

| 100+ | AI reprioritization | Designers, cloud & product teams |

These figures were not marginal adjustments. They represented strategic bets — board decisions taken at scale, often before AI systems were proven in live, complex environments. Below is a list of board assumptions for mass layoffs and why they failed.

Board assumption 1: Routine work equals low judgement

Customer support teams do more than just answer questions. These include:

- Interpret ambiguity

- De-escalate emotion

- Detect emerging issues

- Preserve trust

Similarly, middle management does not merely relay instructions. Their responsibility includes:

- Translating strategy into action

- Absorbing organizational friction

- Flagging when plans are misaligned with reality

By removing these layers, organizations did not eliminate inefficiency. They eliminated sense-making capacity.

Board assumption 2: Speed is the same as productivity

Perhaps the most damaging assumption was the belief that faster output automatically means better outcomes. AI unquestionably increased:

- Response speed

- Content volume

- Analytical throughput

But productivity in real organizations is not measured by output volume. It is measured by:

- Decision quality

- Error rates

- Rework

- Customer trust

- Long-term resilience

By optimizing for speed alone, many enterprises degraded the very metrics that sustain them. By removing people prematurely, organizations reduced their ability to govern the very systems they were betting on. This miscalculation sets the stage for what followed next — regret, reversal, and quiet correction.

6. When reality intervened: regret, reversal, and rehiring

The first phase of AI adoption was loud. The second phase was quieter. After the initial wave of AI-linked layoffs, many enterprises entered a period of operational reckoning. The promised efficiency gains did not materialize at the expected scale. In some cases, performance degraded. In others, risk exposure increased. In most cases, the savings proved fragile. Publicly, very few companies admitted error. Operationally, many corrected course.

Enterprises rarely announce reversals explicitly. Instead, they implement them silently — through rehiring, role redefinition, outsourcing backfills, or the reintroduction of “temporary” human oversight that quietly becomes permanent. The table below captures representative and well-documented cases where organizations either publicly acknowledged AI-led misjudgments or demonstrably reversed course due to operational realities.

| Organization / Category | What was attempted | What failed in practice | Observable outcome |

| Klarna | Replaced ~700 customer-support roles with AI | Loss of empathy, nuance, and issue resolution quality | Human agents reintroduced for complex cases |

| Banking & financial pilots | Automated frontline and decision workflows | Regulatory risk, trust erosion, service failures | Partial rehiring and mandatory human oversight |

| Multi-enterprise surveys | AI-led workforce reductions | Missed ROI, higher rework, lower productivity | Planned rehiring and role rebalancing |

AI systems perform well when problems conform to known patterns. Real-world operations do not. Customer interactions, compliance decisions, and strategic judgements are dominated by:

- Ambiguity

- Emotion

- Exceptions

- Context-specific nuance

Humans excel precisely where averages break down. When organizations optimized for the “typical case,” they became brittle in atypical but consequential moments. What looked efficient on a dashboard became expensive in reality. Many enterprises assumed AI would replace human effort, but customers trusted humans and not AI. In practice, it redistributed it as AI systems required:

- Continuous monitoring

- Output validation

- Exception handling

- Explanation to customers and regulators

- Model retraining and escalation

These tasks demand experienced professionals — not entry-level oversight. By removing experienced staff, organizations increased dependency on fewer, overstretched experts, creating bottlenecks and risk concentration.

7. Why experienced professionals (40+) stand to gain the most from AI

One of the most persistent misconceptions surrounding AI adoption is that it primarily benefits the young — those who are digitally native, tool-fluent, and unburdened by “legacy thinking.”

This belief is not just incorrect, but strategically dangerous. AI disproportionately rewards experience. And judgement is not evenly distributed across age groups — it is accumulated through exposure to failure, evolved knowledge, consequence, and complexity – culminating as experience

Experience is the missing layer in most AI deployments.Professionals with 20+ years of experience carry this knowledge implicitly. They do not need to be told which outputs are irrelevant, risky, politically infeasible, or strategically naive. They recognize it instantly.

AI accelerates this recognition — it does not replace it. Experienced professionals:

- Ask better questions

- Define tighter constraints

- Specify outcomes instead of tasks

- Detect when the model is answering the wrong question

A junior professional may generate ten impressive outputs. An experienced professional will discard nine — and know why. That ability cannot be taught quickly. It is earned over decades.

AI gives less-experienced users a dangerous illusion: the feeling of competence without accountability. Experienced professionals are far less susceptible to this illusion because they have seen:

- Strategies that looked perfect and failed

- Data that was technically correct and practically useless

- Recommendations that collapsed under real-world pressure

For experienced professionals, AI is not a learning shortcut. It is a time-compression engine.

Work that once took months — research, synthesis, iteration — can now be done in weeks, sometimes days, because AI removes mechanical effort from processes they already understand deeply. This is why senior consultants, strategists, creatives, doctors, and analysts often report disproportionate gains from AI adoption, not because they rely on it more, but because they direct it better.

8. Why AI may be a bubble — and where Big Tech miscalculated

Calling AI a “bubble” is often misunderstood as dismissing its capability. That is not the argument RSC wants to establish here, nor suggestive that AI lacks potential. What is questionable is how broadly and how quickly its value was assumed to materialize. The miscalculation was not technological, but rather behavioral and economic.

AI is not the internet. Much of the AI optimism rests on an implicit comparison to the internet. The logic goes like this:

- The internet was once niche, technical, and misunderstood

- It later became universal and indispensable

- AI will follow the same trajectory

This type of analogy is convenient, and wrong. The internet succeeded because it reduced friction without demanding judgement. Anyone could:

- Book a ticket

- Send an email

- Browse information

- Participate in social media

No specialized cognitive skill was required. The internet did not ask users to evaluateoutputs. It simply connected them. AI is fundamentally different. AI demands:

- Clear intent

- Problem framing

- Output evaluation

- Responsibility for consequences

These are not mass skills. They are professional skills. Big Tech built AI narratives around universal empowerment:

- “Everyone will be more productive”

- “Anyone can be a creator”

- “AI will democratize intelligence”

Such narratives were commercially necessary because valuations require scale. Enterprise-only adoption is never enough to sustain consumer-facing hype cycles. Why would investors be interested right? But reality intervened. The majority of users engage with AI in low-stakes, low-responsibility ways such as:

- Entertainment

- Casual content creation

- Image generation

- Social media experimentation

- Novelty use cases

There is nothing wrong with this, but it does not translate into structural productivity gains. High-value AI use — the kind that transforms organizations — requires:

- Analytical thinking

- Domain expertise

- Accountability

- Tolerance for ambiguity

- Guidance for research, compliance and useful insights

Such prerequisites to effectively use AI immediately narrows the addressable audience. Unlike the internet, which broadly flattened access, AI concentrates advantage. Those who already possess experience, strategic thinking ability creative discernment, and decision-making authority benefit exponentially. Those without these attributes gain surface-level outputs, but little durable advantage.

This is why AI adoption curves look impressive in usage statistics but underwhelming in measurable productivity data at the macro level. In its most durable form, AI behaves less like a smartphone and more like heavy industrial infrastructure. It is:

- Expensive to deploy properly

- Dependent on high-quality inputs

- Sensitive to governance failures

- Most valuable in complex, high-stakes environments

In other words, AI is structurally B2B and enterprise-centric. Like a heavy cargo freight train, it moves enormous value — but only along well-defined tracks, under expert supervision, and at significant cost. Expecting it to transform everyday work for the general population was never realistic.

9. Why extreme positions on AI are intellectually irresponsible

By this point, the pattern should be clear. The most vocal positions in the AI debate — absolute enthusiasm or absolute rejection — share a common flaw – they avoid responsibility. Pro-AI absolutism leads to premature automation, loss of institutional memory, and brittle systems. Anti-AI absolutism leads to stagnation, missed opportunity, and strategic irrelevance. In both cases, the organization becomes less capable of responding to reality. This is why the most resilient institutions historically have never been the most enthusiastic adopters nor the loudest skeptics. They have been disciplined integrators.

Taking the middle ground does not mean being cautious or indecisive. It means demanding more from leadership. The defining question is: Who is qualified to decide when AI should be trusted — and when it should not? That question has only one credible answer: People with experience, judgement, and accountability. Everything else is merely noise.

10. Conclusion: The correction phase — and the RSC prediction

The last two years will likely be remembered as the impulsive phase of enterprise AI adoption.

Encouraged by aggressive narratives from technology companies, amplified by investor pressure, and accelerated by fear of competitive disadvantage (FOMO), many large organizations made a critical mistake – they treated AI as a replacement for human judgement, rather than as a multiplier of it.

Layoffs were executed not because AI had proven itself in complex, real-world conditions, but because it appeared capable in controlled demonstrations. Speed was prioritized over stability. Cost reduction was prioritized over institutional memory. And in the process, many organizations weakened the very capabilities required to govern powerful new systems. RSC maintains that AI did not fail. What failed was how it was positioned, deployed, and governed.

The corrections are already underway, quietly albeit, where organizations are rehiring people for customer facing roles and governing oversights. Enterprises are rediscovering a truth that should never have been forgotten: Automation increases the cost of bad decisions.

Therefore, it increases the value of good judgement. AI accelerates everything — including mistakes.

Decision-making in the real world is not a computational exercise. It is a commitment under uncertainty — legal, reputational, ethical, cultural, and financial. AI can inform such commitments but cannot own them. By laying off experienced professionals under the assumption that AI could absorb judgement, many organizations created a vacuum that technology could not fill. That vacuum is now being felt.

The RSC prediction: the return of experience — at a premium!

At RSC, we take a clear and unapologetic position: Highly creative and analytical professionals with more than 10+ years of real-world experience will be rehired — not at parity, but at a significant premium. We anticipate:

- 3× to 20× increases over prior compensation levels

- Narrower but more powerful roles

- Explicit authority to govern AI systems

- Greater accountability — and greater leverage

These professionals will not be hired to “use AI.” They will be hired to direct it, constrain it, and decide when it should be ignored. Such capability is rare, and rarity commands a premium. The durable model that survives the correction phase is not radical — it is disciplined where:

- Humans define intent and boundaries

- AI accelerates exploration and execution

- Humans retain override authority

- Accountability remains human

- Experience governs scale

The need for AI domestication is imminent. It simplifies what should be governed, debated, and continuously corrected. Real innovation does not come from surrendering control to machines, nor from refusing to engage with them. It comes from experienced humans working in partnership with intelligent systems, each doing what they are uniquely capable of. AI is not the author of meaningful work. It is the amplifier. And in the real world — where consequences matter — only those who can combine human judgement with machine speed will define what comes next.